Those familiar with Joe’s story know that he came to the United States in 1959 thanks to a scholarship to the Berklee School of Music. Why, at the age of 25, did he apply for study at a school in the United States? In his native Austria, Joe was considered one of the top jazz musicians, but opportunities to play jazz were limited, as was exposure to visiting American musicians. Joe understood that to realize his ambitions, he would ultimately need to come to the United States. The Berklee scholarship was his ticket.

He applied for the scholarship after reading an announcement in Down Beat magazine. “My friends and I used to go to the English Reading Room in Vienna to read Down Beat,” he told Conrad Silvert in 1978. “There were maybe two copies in the whole city, but it was our main connection to find out about all the great musicians and maybe gain a little knowledge about the English language. I still read it every issue.”

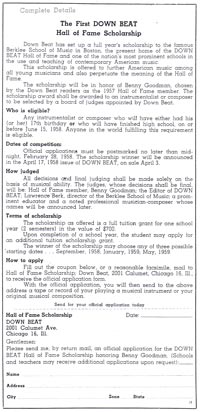

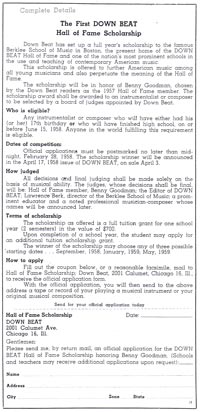

I’ve often been curious about this. Last weekend I was at the library and I decided to look up the 1958 issues of Down Beat. Sure enough, the January 9 issue contained an announcement for “The First DOWN BEAT Hall of Fame Scholarship.” (Click the image above-right to see a large version.)

Down Beat has set up a full year’s scholarship to the famous Berklee School of Music in Boston, the present home of the DOWN BEAT Hall of Fame and one of the nation’s most prominent schools in the use and teaching of contemporary American music.

This scholarship will be in honor of Benny Goodman, chosen by the Down Beat readers as the 1957 Hall of Fame member. The scholarship award shall be awarded to an instrumentalist or composer to be selected by a board of judges appointed by Down Beat.

Per the instructions, Joe requested an official application form and submitted a recording of the Woody Herman tune “Red Top” that he had recently made with the Fatty George band. He had to do this by Feburary 28, after which came a three-month wait to see if he won.

Down Beat promised that the winner of the scholarship would be announced in the April 17 issue. Who knows how long it took for a copy to arrive in Vienna. Joe would have been full of anticipation, and perhaps apprehension, when it finally did arrive. He must have scoured every page, only to find nary a word about the scholarship results.

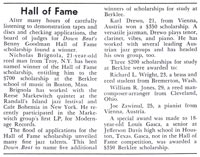

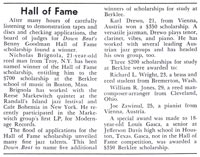

That wouldn’t come for two more issues, when it was finally announced that Nicholas Brignola, a “21-year-old reed man from Troy, N.Y.,” had been named the winner of the Hall of Fame scholarship, entitling him to $700 in tuition for two semesters of study at Berklee. Joe wasn’t a good reader of English at that time, but he probably quickly determined that he didn’t win. Nevertheless, he would have scanned the rest of the article hoping to see his name, and there, near the end, it appeared.

“The flood of applications for the Hall of Fame scholarship unveiled many fine jazz talents,” the article said. “This led Down Beat to name five additional winners of scholarships for study at Berklee.” Two applicants received $350 scholarships; Joe’s name was the last one listed among three musicians who received $200 scholarships.

It was a close call, but Joe had his opening to the United States, provided he could muster the funds to travel to, and live in the US for four months. At the time, this was no mean feat. But in early January 1959, he boarded a ship for the journey across the Atlantic, with a suitcase, his Berklee scholarship, his bass trumpet, and $800 in cash. “I knew that it wouldn’t be easy,” he once recalled, “because I had no relatives, didn’t know a single person in America. But when I came over on the boat, I did it with the purpose to kick asses.” The rest, as they say, is history.

What of the other musicians who received scholarships? Nichalas Brignola, the actual winner, went on to have a fine 45-year career before his passing in 2002, cutting some 20 albums under his own name. Biographies of Brignola never fail to mention that he was the winner of the 1958 “Benny Goodman” scholarship.

A “special award” of $350 was made to 18-year-old “Louis [sic] Gasca, a senior at Jefferson Davis high school in Houston, Texas.” After attending Berklee, trumpet player Luis Gasca went on to play with some of the biggest names in jazz and pop, recording his own albums using the likes Herbie Hancock, Carlos Santana, Joe Henderson and Stanley Clarke. However, drug addition took its toll and he dropped out of the music business.

Along with Zawinul, Richard L. Wright and William R. Jones each won $200 scholarships, but I haven’t turned up any information about them.

I’ve saved the most intriguing name for last. “Karl Drewo, 21, from Vienna, Austria won a $350 scholarship. A versatile jazzman, Drewo plays tenor, clarinet, vibes, and piano. He has worked with several leading Austrian jazz groups and has headed his own group, too.” That’s right. One of Joe’s Viennese pals also applied—and did better than Joe did! In its short bio of Drewo, Down Beat understated Drewo’s age, but they got the rest of the details correct.

Indeed, back in Austria, Drewo and Zawinul traveled in the same circles and played in the same bands. You can hear them both on the album Joe Zawinul and The Austrian All Stars 1954-1957. They even formed their own band together. Clearly, the two were pretty tight, and when Joe talked about reading Down Beat with his friends in the English Reading Room, no doubt Karl Drewo was one of those friends. They would have encouraged each other to apply, and doing so jointly would have helped overcome the teasing from their fellow musicians who neither had the ability nor the nerve to play jazz in America.

Drewo not only got the more prestigious award, but a much more thorough write-up than Joe as well. Down Beat simply described Zawinul as “25, a pianist from Vienna, Austria.” Drewo went on to have a successful career in Europe and has an annual festival named after him in Austria. He died in 1995. So far as I can tell, he never took advantage of his scholarship.

Of course, ultimately, neither did Joe. Within a couple of weeks of arriving at Berklee, one of his professors recommended him for a club gig opening for Ella Fitzgerald. That led to him auditioning for Maynard Ferguson the next day, and he never looked back.